For 2022’s Black History Month CIHT are highlighting key figures that helped changed the Transport and Highways sector for the better. This year’s theme for Black History Month is ‘Time for Change: Action Not Words.’ The theme shows this years Black History month is more important than ever. It is not just a month to celebrate achievements it is a time for continued action to tackle racism and ensure Black history is celebrated all year round.

Join other savvy professionals just like you at CIHT. We are committed to fulfilling your professional development needs throughout your career

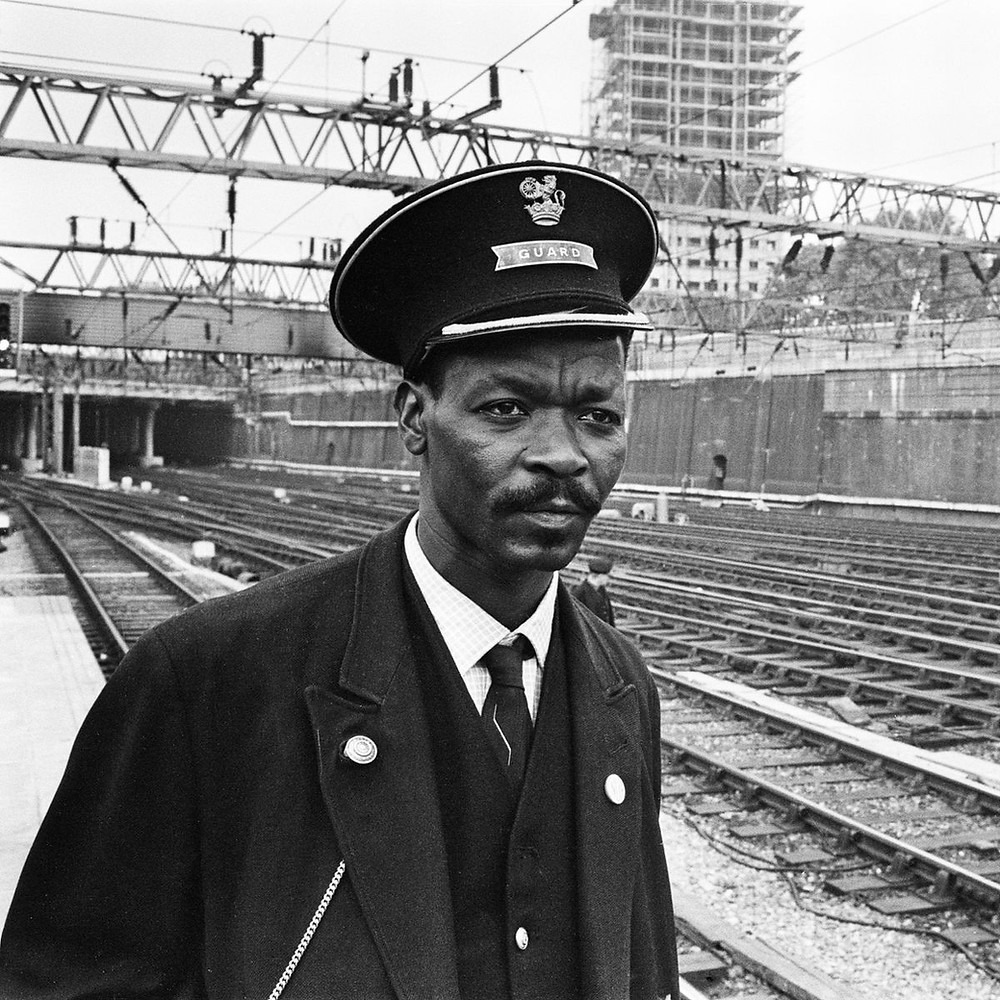

As part of the Windrush generation Asquith Xavier came to the UK in 1958 after a request from the British government for people in the Caribbean to move to Britain to help cover labour shortages. Asquith was employed by the British Rail as a porter and shortly after was promoted to a guard’s role at Marylebone. 8 years later, the freight link at Marylebone was closed. He then applied for a transfer to Euston station. He was declined because of an unofficial ‘colour bar’ which didn’t allow Black people to have customer facing roles.

This was just the start of a big change that later followed in the transport sector. Asquith started his campaign to end discrimination within the British Rail. Later in 1965 the Race Relations Act was passed making it illegal to discriminate on the grounds of race, ethnicity, or colour in public places. However, railways were not considered public so the fight for Asquith continued. With the help of the Secretary of State for Transport Barbra Castle and the NUR Branch Secretary Jimmy Prendergast Asquith became the first Black guard at Euston station in the summer of 1966.

Asquith campaign not only led to the strengthening of the Race Relations Act 1968 the Commission for Racial Equality was created.

His win also came at a cost, Asquith required police protection to and from work because of the race hate and threats to his life he received from the public.

Asquith sadly passed away in 1980 but his legacy and strength of character is still remembered and his fight for equal opportunities for the Windrush generation and future generations lives on.

From 1956 to 1970 London Transport recruited around 6,000 people from British colonies in the Caribbean to the UK. During this time, many West Indian women were also recruited, most of which were assigned to catering roles. Women were not allowed to be bus drivers they were however given bus conductor roles. In our search for Black women in transport we found Agatha Claudette Hart, one of the first recorded female bus conductors. Agatha worked as a bus conductor at Stockwell bus garage.

There is little information on Agatha and other women alike which shows how few opportunities women had. Black History Month is a good time to reflect on the positive changes that have been made and to think about what action can be taken now for future generations.

Without these pioneering people in transport not only could the sector have looked very different but changes to law and society could have taken a different path. For continued change to happen we need actions.

Photo credit: Dr Heinz Zinram

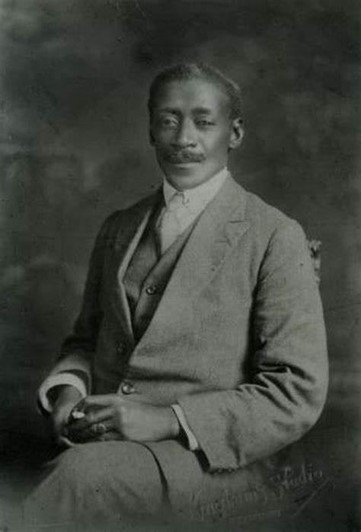

Joe was born in Kingston, Jamaica in 1997 and began working at a young age as a stable hand for a Scottish doctor. Joe’s employer moved to Britain in 1906 and Joe agreed to go with him. When first arriving in England Joe was driving coach and horses and later learned to drive motor vehicles, working as Dr White’s chauffeur. In 1910 Joe joined the largest bus operation in London, the London General Omnibus Company. He trained at Shepherd’s Bush garage and became qualified as a spare driver.

Joe faced racism from his colleagues and was wrongfully suspended for speeding by a racist boss. His proven track record led to this being dismissed but this certainly was not the last time Joe was subject to racism in the workplace.

Later, Joe got married and moved to Bedfordshire where he continued to work as a bus driver. As World War One began Joe volunteered to join the Army Service Corps. From 1915 to 1919 he served in the army as an ambulance driver on the western front. Upon returning from the army Joe returned to bus driving and became a taxi driver in 1949, retiring in 1968.

Joe was a respected figure in Bedford ad featured in TV programmes and local newspapers after being interviewed for ‘The Un-melting Pot’ a book by John Brown. The book featured a chapter about Joe and Margaret Clough and was a study on Bedford’s immigrant population. He sadly died in 1976 at the age of 89.

Photo credit: The Virtual Library

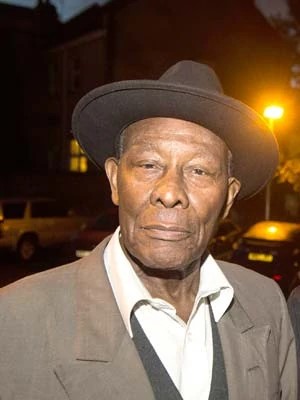

Roy Hackett was born in Kingston, Jamacia and moved to the UK in 1952 and later settled in Bristol. Alongside Paul Stephenson, Prince Brown, Owen Henry and Audley Evans he helped organise the Bristol Bus boycott of 1963. The boycott lasted 4 months and was part of a campaign to stop using Bristol Omnibus Company buses because of its refusal to employ Black and Asian people. The campaign gained huge amounts of attention nationally and was supported by many politicians. Students from Bristol University also held a protest in support. Around 3,000 people joined the boycott that was partly inspired by the 1955 Montgomery action.

The protests in 63 paved the way for the Race Relations Act in 1965 and forced the Bristol Omnibus Company to change their policies.

Roy also went on to co-found the Commonwealth coordinated Committee which put pressure on the council to make improvements to employment and housing.

He was appointed an MBE in 2020 and later died in August 2022. Roy was a community hero and helped overcome adversity and racism. He once described his early years in the UK as 'a dog's life' but turned his life into a legacy and his fight still lives on.

Photo credit: Bristol fandom

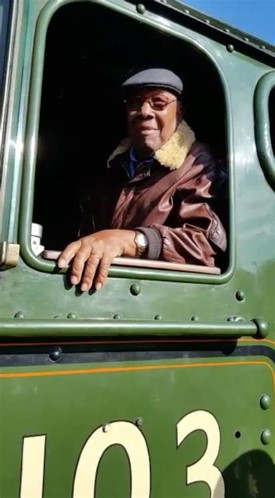

Wilston arrived in London in 1952 after his father’s sudden death in Jamaica. He landed a job repairing the railways that had been damaged during World War Two. At the time driver roles were reserved for white men but later in 1962 he passed his exams and became the first Black train driver.

However, this sparked a furious reaction from his fellow colleagues many of which refused to work alongside him. Many were concerned that a Black man had disrupted the status quo within the rail industry.

Never one to miss an opportunity, in 1966 Wilston immigrated to Zambia where experienced train drivers were needed.

He sadly passed away in 2018 at the age of 91.

In 2021, a blue plaque was unveiled at London’s Kings Cross station to commemorate Wilston’s career and achievements as Britain’s first Black train driver. Wilson’s legacy lives on and he opened doors for future generations to take up important transport roles.

Photo credit: Black History Month UK

Want to learn more?

To learn more about Black History Month visit here.

If there are any Black transport figures you would like to highlight, please contact communcations@ciht.org.uk.

Join other savvy professionals just like you at CIHT. We are committed to fulfilling your professional development needs throughout your career

{{item.AuthorName}} {{item.AuthorName}} says on {{item.DateFormattedString}}: