In January CIHT launched a survey on climate change issues with the purpose of gathering knowledge and views from highways and transportation professionals. The response was overwhelming – a total of 791 people participated in the survey. We present an overview of the survey here.

Join other savvy professionals just like you at CIHT. We are committed to fulfilling your professional development needs throughout your career

In January CIHT launched a survey on climate change issues with the purpose of gathering knowledge and views from highways and transportation professionals. The response was overwhelming – a total of 791 people participated in the survey.

The survey response has already and will continue to support CIHT in several ways; we have used it to inform our response to the Committee on Climate Change’s Sixth Carbon Budget Call for Evidence and our 2020 Budget submission, Comprehensive Spending Review representation and we will continue to use it for consultation responses. Later in the year we will also contribute to the development of the Transport Decarbonisation Plan.

Changing highways and transport for the better is not just about influencing decision makers, but just as much about collaborating and sharing knowledge within the profession.

This blog is written to signpost to relevant developments within the different topic areas and link to the work CIHT is doing in the different areas.

If you have any comments please feel free to take part in the conversation on CIHT Connect (available to CIHT Members).

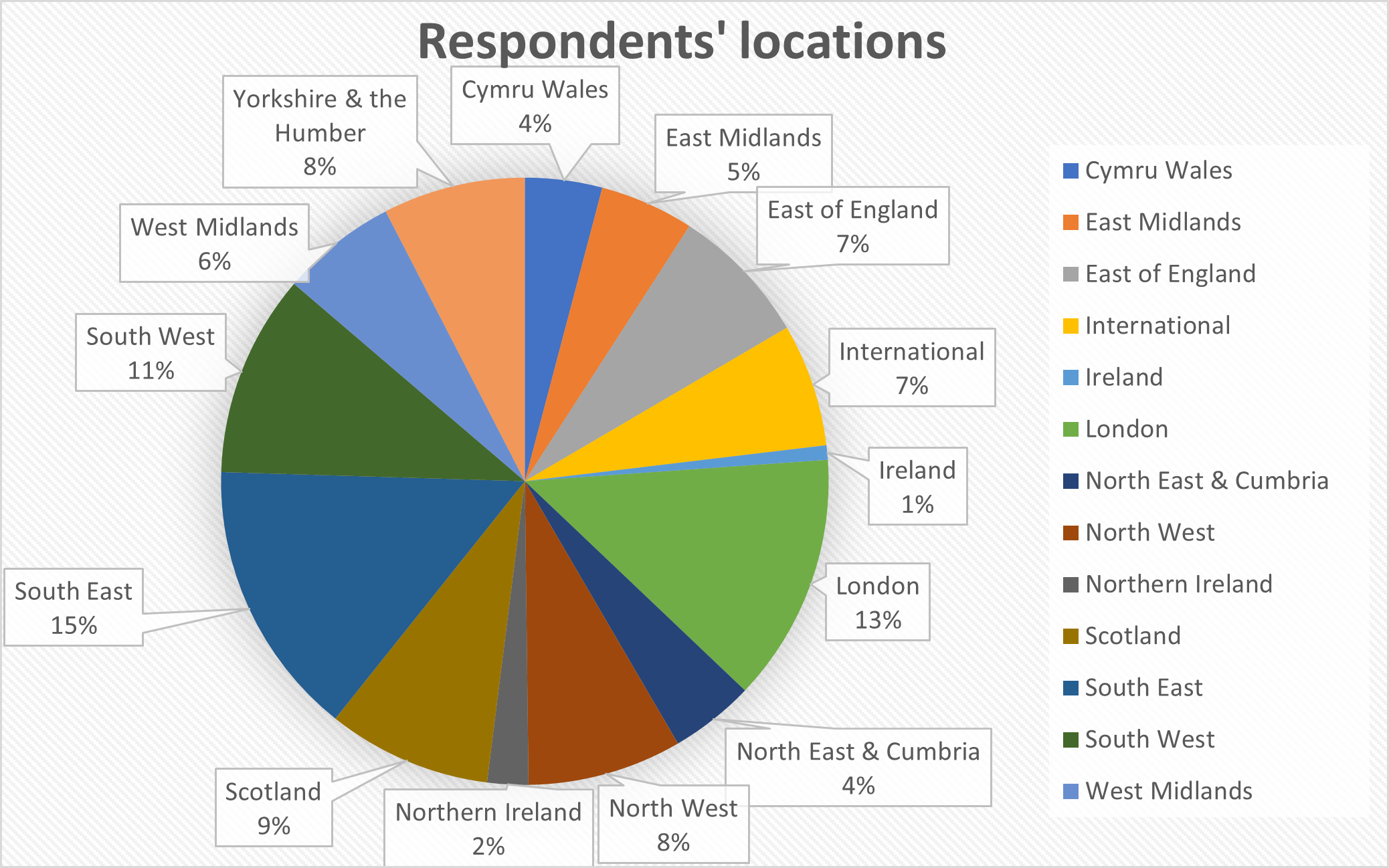

A total of 791 people from the UK and abroad participated. People from the public and private sector, academia, Sub-national Transport Bodies and government shared their knowledge. Of the total respondents 51 were internationally based including members based in China, New Zealand, Hong-Kong, Brunei, Bahrain and many more.

The overarching theme of the survey was about transport and climate change. The questions were grouped in to three themes. These were society, policy and transport specific.

Society - The Government Office for Science note that by 2040 nearly one in seven people is projected to be aged over 75. This demographic shift will shape how public services are planned and will influence every government department. Without significant improvements in health, the ageing UK population will increase the proportion of people who are of ill-health and disabled. We asked about the role of transport in this and other developments related to changes to our society.

Policy - These questions related to specific policies, either existing or those proposed in consultations. We also asked what policies need to be implemented to transition the UK to a zero-emission economy.

Transport specific - We asked about specific transport modes and technologies, to get an understanding of the impact these could have on transport networks. Key words were active travel, public transport and automated vehicles.

From the responses it was clear that providing for the necessary transport needs that an older and less mobile population will have is going to be important going forward. However, the proposed solutions would be of equal benefit to the wider population and the outcomes sought are ones we should be trying to achieve regardless, that is, an inclusive transport system that is not restrictive to anyone.

Part of the challenge that comes with an ageing population in terms of transport is that as we age we naturally lose some of our personal mobility and travelling independently, even for the most basic needs, can become difficult. We do not however lose our aspirations for a high quality of life as we get older and our needs for shopping, visiting friends and family, hobbies or doctors visits remain. If we are not able to get around, we will be isolated and experience loneliness. Reinforcing the importance of this, countering the epidemic of loneliness is recognised as one of the main objectives of ‘An Ageing Society’, and is addressed as one of the five grand challenges within the government’s Industrial Strategy.

New approaches to mobility must consider the human factors, the user requirements across all age groups and ensure that new and existing systems are accessible. Transport strategies today need to build in opportunities for: enhanced mobility for the older generation, spatial planning to support access to transport hubs from rural and urban areas, and road and street design that allows all user groups to travel in the public domain.

Streets and other public places need to cater for all users. Firstly, the condition of the streets and pavements themselves must be in a condition that allows for the less mobile pedestrians, including those on disability scooters, to use them safely. Street layouts should be simple and calming. They can generally also become more inclusive by making pedestrian crossings safer by allowing longer times to cross. For older people, places to rest is also important. Some respondents also suggest changes to 20mph speed limits in all urban areas.

CIHT is currently in the process of revising Manual for Streets, a project that will engage with a wide range of stakeholders to help ensure that future streets cater for the whole population.

Improving public transport was one of the most frequently cited measures to overcome the challenges, especially as its current state is deemed far from good enough in many, some would say most, parts of the country. One of the most frequent reasons for not using public transport among those 65 years old and over, is that it is not convenient and does not take you where you want to go. Service needs to become more reliable, comfortable and accessible both in terms of actual bus and train design and service, but also in terms of route planning. Making sure that public transport is available in the necessary locations, both in rural and urban settings, is one of the main tasks in hand. Many respondents pointed out that rural areas must not be neglected. Affordability is another important aspect of a good public transport system, which can become particularly tricky in rural settings where there is not a critical mass of users, but you still want to provide subsidy and concessionary fares.

Making sure that transport systems are integrated and connected is also important, and good transport interchanges will play a role in this. The planned South Wales Metro in Cardiff was mentioned as an example of where emissions might be moved from the city centre, but if not thought about holistically, you risk simply displacing the emissions to stations along the metro route if good public transport is not provided to those stations.

Since this survey was launched, CIHT has in its pre-budget submission called for increased funding for public transport which has seen big cuts in recent years inevitably causing a deteriorating service. The government has since announced increased funding for buses, a National Bus Strategy is expected later in the year and a Future of Mobility: Rural Strategy is being developed.

See CIHT guidance Buses in Urban Development here.

Another point frequently made was the need to better integrate spatial and transport planning, primarily to make transport more sustainable and healthy. A big challenge to achieve this is the balancing act of providing enough new housing, something that councils are under pressure to do, while making sure that developments for new housing are sustainable in transport terms. The pressure to deliver enough housing too often overrides sustainable transport objectives. Supporting this is the report A Housing Design Audit for England (2020) by UCL Professor Matthew Carmona that found nearly three quarters of 142 developments surveyed should not have been given planning permission, in many cases on the grounds of not providing for sustainable travel modes.

This was also echoed in the survey responses where a call to stop approving 'traditional' housing developments on peripheral or rural sites was made. Transport investment by government could focus on regional projects like the 'Northern Powerhouse' and resist 'predict and provide' policies like extending and widening motorways. Local authorities can emphasise place rather than mobility, as for example in Brighton's 'car free centre' proposal.

Another hindrance to the integration of planning and transport is a cultural resistance, a ‘this is how it’s always been done’ approach that seems to be prevalent according to survey respondents.

In addition, there are wider issues which make achieving this difficult and include:

One of the main barriers mentioned was that there is little incentive for landowners to engage with this agenda. Integrated land use can be much more expensive and harder to find investment for. It also requires more cooperation which can further increase cost and adds time to projects.

The fact that the need for new housing stock is the main priority means that it often overrides any considerations of sustainable transport.

Low standards for what is acceptable in terms of accessibility by sustainable modes, means that sustainability can often become a tick-box exercise for developers. Resourcing within local authorities is also a significant issue in terms of creating the necessary plans and being able to challenge development proposals.

Most of the above issues arise from a planning system that is not fit for purpose. As many will be aware the government is currently consulting on its planning process. You can read CIHT’s response to the consultation on the Planning White Paper here.

See CIHT’s Better Planning, Better Transport, Better Places here.

Many commented that a fair transition to ‘net zero’ would be almost impossible and that there would be winners and losers of a transition to net zero. But there were also many suggestions as to how a fairer transition could happen. From wide ranging interventions such as an emissions unit, or rationing, a system for putting an upper limit on individuals’ consumption running parallel to our monetary system, to smaller and more focussed interventions.

Some meant that the general attitude towards non-sustainable travel modes, and the unintended negative consequences of these, needs to change in a similar fashion to how smoking or exposing others to passive-smoking, has become frowned upon in the last twenty years.

A stigma that public transport is for those on lower incomes was also mentioned as a ‘behaviour’ that deterred some people from getting on the bus or train.

Personal carbon budgets, or rationing, for consumers was one idea that was mentioned frequently, however such a society-wide policy would be beyond CIHT’s remit to explore. On a related note though, road pricing was mentioned as a way to achieve at least a reduction of emissions. When combined with the idea of having to deliver a fair transition, road pricing risks disproportionately affecting lower income groups whose budgets will be relatively more affected by such schemes. Switching to electric vehicles is not just a matter of wanting to do so, but also having the means to do so and for it to be a practical solution for your transport needs.

A challenge that will require some consideration in this aspect is if subsidies are likely to be required at the point of vehicle purchase, and whilst there is a trickle down of the likes of electric vehicles over the next 10-20 years, some flexibility in the taxation and pricing of fossil fuels may be required to take account of those sections of the population that are reliant on the use of such vehicles. It would not really be equitable therefore to have different levels of road pricing for different vehicles, where those who have no choice but to use an older vehicle using traditional fuels were penalised over those who'd been able to take advantage of a subsidy to own a newer say wholly electric vehicle.

Most respondents had a positive view on road user charging. They saw it as essential and the key lever for managing demand. Some argued that it needs to be a comprehensive user-friendly system that integrates and replaces all existing taxes and charges e.g. VED, road tolls, parking permit fees. In a recent CIHT webinar, 76% of respondents were also in favour of a nation-wide road pricing system.

It needs to be dynamic in time and location to incentivise desirable behaviours and penalise undesirable behaviours. It must also be clear and transparent so that individuals understand what they are paying for and why e.g. they pay more to drive in urban areas at peak times which is directly used to subsidise public transport services.

Others argue that the impact in demand management terms is likely to be limited because the elasticities of demand are not favourable in this regard. A flat rate per mile/km which could then be added to by local authorities for specific geographical areas, such as low emission zones or built-up urban areas was more widely suggested. The local element of the charge should then be hypothecated to the relevant local authorities and ring-fenced for sustainable transport schemes, as an example.

As mentioned, road charging schemes risks affecting the population disproportionately. Some respondents were against road user charging on the grounds that it is inequitable; people who can afford the charging will continue to drive while less fortunate members of society will not. It has been questioned whether a potentially vastly improved public transport network as an alternative for those who can no longer afford to drive privately is a fair solution. Some argued that such schemes could be punitive and would further increase the chasm between the richest and poorest in terms of accessibility to jobs and opportunities.

CIHT has in its Budget and Comprehensive Spending Review representations called for the government to start investigating options for some form of road user charging. In CIHT's recent statement to the Chancellor's Spending Review, CIHT Chief Executive Sue Percy said that "Although no specific mention was made of road pricing, CIHT sees benefit in consideration of a form of pricing system to address not just falling fuel duty revenues but as a measure to achieve carbon reduction.”

Before going into the comments made to this questions, it would be useful for context to take a quick look at some data from the government’s National Travel Attitudes Study from 2020 which showed that a majority recognises the importance of changing towards more sustainable behaviours. The majority is also increasing.

The majority of the responses to CIHT’s survey agreed that individual behaviour could have a significant effect on reducing carbon emissions, but many also noted that the government and businesses have an equally large role to play. The rural and urban divide was also mentioned here, as it is much easier for most urban dwellers to take more sustainable transport choices.

The fear that many older car users have become so entrenched in their behaviour, also meant that some respondents thought that focussing on younger generations to change their behaviour was the most feasible way of changing behaviours. Culture and habits are very challenging aspects to change and it will be difficult to do so without leadership. Education will play a key role in establishing new norms for the younger generation.

In general, as has already been mentioned, a better balance in terms of cost for users of using different transport modes needs to be implemented. The lowest polluting options should also be the cheapest. Several respondents had examples of how car ownership can in many cases be cheaper than public transport.

Traditional predict-and-provide methods of transport planning need to go in favour of decide-and-provide approaches. Continuing to build roads was mentioned by many as being in opposition to the goal of achieving net-zero. A suggestion was made that transport assessment should be requested to achieve certain modal splits.

See CIHT Futures report here which discusses the predict-and-provide and decide-and-provide paradigms.

Many suggestions went beyond the traditional remit of transportation professionals but were about policies that affect how transport is being used. Measures mentioned by respondents included increasing working from home policies, making schools consider and coordinate location when deciding intake of pupils, better access to health services and GPs instead of centralisation and more.

Some specific examples included:

Low emission zones were also mentioned to be a challenge for high streets as fewer people are then able to reach them.

As was mentioned by several respondents, active travel can and will have the largest impact in urban areas, equally quite a few respondents said that overall it would not have a significant impact in efforts to decarbonise transport. In rural areas active travel modes are far less feasible and different solutions will have to aide the transition to a carbon neutral transport system in those areas.

Providing the appropriate cycling and walking infrastructure is imperative to achieving success in this area as road safety is a major concern and deterrent for many in terms of getting on the bike. But many urban dwellers can already cycle and have reasonable infrastructure in place, so a cultural or behavioural change might also be required. England used to have many cyclists before the car took over significantly.

Active travel should also be promoted as a healthy transport option and not just in terms of its sustainability. This message should not only come from the transport sector but also from the health sector.

Since this survey was conducted the government has released its Gear Change plan and the Local Transport Note 20/1 on Cycle Infrastructure Design.

CIHT are currently involved with the development of an online course about transport and health aimed at practitioners in both areas.

In 2016 CIHT released a report: A Transport Journey to a Healthier Life, that discussed how transport policy and procedure can contribute to the health (including mental health) and wellbeing agenda.

This is of course highly uncertain at the moment, and probably many years away. There are still many factors that are unknown, such as who will the owners of autonomous vehicles be, will they be privately owned or operated under taxi-like business models, how will they be regulated etc. It is possible that they will have a major impact, either positive or negative. This will very much depend on how they are regulated and how available they will be.

Many thought that autonomous vehicles might increase transport demand as they provide a more convenient, potentially cheaper transport option. Users will be able to do other things whilst riding in AVs and therefore potentially be more inclined to take longer journeys.

In CIHT’s response to the Law Commission’s Automated Vehicle consultations we have called for these vehicles to be regulated in a way so that they work positively in conjunction with relevant transport authorities’ visions for their transport network. CIHT wants these vehicles to be an aid to our vision for transport as opposed to being led by the vehicles and what they can do.

{{item.AuthorName}} {{item.AuthorName}} says on {{item.DateFormattedString}}: